Warrick Invasive Species Partnership (WISP) is a local working group consisting of citizens and organizations within the county coming together to bring awareness of the damage that invasive species cause to our environment, health, and economy. This group focuses on invasive plant identification and detection, removal, as well as learning about native alternatives.

This group is welcome to any and all! To join simply join us at one of our regular meetings or events or fill out a contact form below if you have questions.

This group is welcome to any and all! To join simply join us at one of our regular meetings or events or fill out a contact form below if you have questions.

upcoming 2023 Weed wrangles:

- October 7, Castle North Middle School

Common Warrick County Invasives

Burning Bush

Burning bush, Euonymus alatus, was introduced to the United States in the 1860s from China, Japan, and Korea. It is still commonly planted for its beautiful red fall foliage and as a dense hedgerow. It was documented escaping cultivation and establishing in natural areas in the 1970s. Despite knowing its invasive habits it is still a popular landscaping shrub.

Burning bush, winged euonymus, or winged burning bush is easy to identify, especially in the fall. The stems have corky ridges or wings that grow out from the stem. The leaves and branches grow opposite of each other. Leaves are widest at the middle and taper to each end. Leaves turn a brilliant red in the fall. Burning bush produces greenish-yellow flowers in the spring to early summer and red to orange fleshy seeds in the fall.

Burning bush, winged euonymus, or winged burning bush is easy to identify, especially in the fall. The stems have corky ridges or wings that grow out from the stem. The leaves and branches grow opposite of each other. Leaves are widest at the middle and taper to each end. Leaves turn a brilliant red in the fall. Burning bush produces greenish-yellow flowers in the spring to early summer and red to orange fleshy seeds in the fall.

Burning bush can quickly spread and invade natural areas. Burning bush can tolerate conditions from full sun to full shade. Birds eat the fruits, spreading seeds to neighboring natural areas. The dense growth of this shrub quickly shade out smaller native plant species leading to a monocultural understory. Deer prefer foraging on native species, which reduces native competition for the burning bush.

Native Alternatives

Native species that make great alternatives are Eastern Wahoo, Buttonbush, Fragrant Sumac, and Red Osier Dogwood.

Japanese Honeysuckle

Japanese honeysuckle, Lonicera japonica, is a perennial woody vine that spreads by seeds, underground rhizomes, and above ground runners. It has opposite oval (sometimes lobed) leaves that are semi-evergreen. Flowers are fragrant, two-lipped, and grow in pairs. The berries are black.

Japanese honeysuckle was introduced to the US in 1806 on Long Island, NY. This invasive species forms dense blankets that shade out native vegetation. It quickly twines up trees and shrubs, completely covering them. It is limited in the eastern US by frigid winter temperatures to the north and droughts to the west. It is found in all 92 Indiana counties but is more aggressive in the southern parts of the state.

native alternatives

Bush honeysuckle

Asian bush honeysuckle sums up several species of invasive shrubs: Amur (Lonicera maackii), Tartarian (L. tatarica), Morrow's (L. morrowii), and Belle's (L. X bella) honeysuckle. Amur honeysuckle is the only one currently found in Warrick County, but all species can be found in Indiana. Each have arching branches that can reach 6-15 ft tall, opposite leaves with paired tubular flowers and berries, and hollow branchlets. Amur and Morrow honeysuckles have white flowers, Tartarian have pink flowers, and Belle's vary from white to deep rose flowers.

These species are easy to spot as they are one of the first plants to green in the spring and one of the last to lose their leaves in the fall. Bush honeysuckle grows so densely that they shade out the entire forest floor, often leaving nothing but bare soil. This means great reductions in food and cover for small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and birds. Nest predation has been found to be much higher in honeysuckle than native cover. Dense infestations can stop tree regeneration.

native alternatives

Autumn olive

Autumn olive, Elaeagnus umbellata, is a medium to large deciduous shrub with silvery underside to its leaves. Its leaves are alternate, oval to lanceolate, untoothed and grow 1-3 inches in length. It has small, light-yellow flowers in the spring and small, round fruits that are reddish to pink with silvery spots.

Autumn olive have rapid growth, fruit prolifically, can thrive in poor soils, and are widely dispersed by birds. One plant can produce up to 80 pounds of fruit in one season! It can quickly outcompete natives.

Native alternatives

Bradford/callery pear

Bradford pears were brought to the US for yards and landscaping for their rapid growth, dense foliage, and profusion of flowers in the spring. When originally introduced the trees were self-sterile, but they began cross-pollinating with non-sterile varieties. The leaves are heart-shaped to oval, finely round-toothed on the edge, shiny, and leathery growing alternative along stems.

Bradford pears grow in dense, thorny thickets in wild areas, outcompeting natives such as the Eastern redbud and serviceberry. Bradford pears have a tendency to split, fall apart, or uproot under wind and snow.

native alternatives

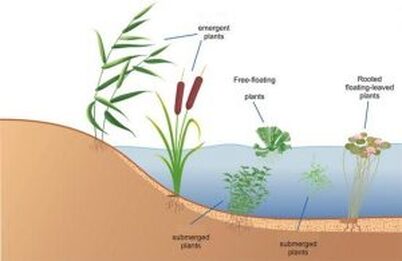

Common reed / phragmites

Common reed (Phragmites australis ssp. australis) is a pervasive invasive in Warrick County. It is a warm season, perennial grass that can grow up to 20 feet tall. Seedheads are large and full, persisting through the winter. Phragmites grows on the edges and into wet areas: roadside ditches, ponds, lakes, along railroad tracks. There is a native species of reed (Phragmites australis ssp. americanus) in northern Indiana that can be distinguished from the invasive species by purple stems, red leaf collars, fungal spots, and smaller seedheads.

Common reed grows quick, tall, and thick, readily outcompeting native vegetation. In Warrick County it grows in dense stands along the edges on mine pits, roadsides, and railroad tracks.

native alternatives

Japanese Knotweed

Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) was introduced to the US in the late 1800s as an ornamental plant. Knotweed is an herbaceous perennial that looks like a shrub, growing between 3-9 feet high. Stems are reddish, ridged, and hollow. Leaves are alternate and 2-3 inches wide. It flowers in late summer, producing small white to green flowers on a spike. Knotweed prefers to grow in moist, open to partially shaded areas such as riverbanks, wetlands, roadways, hillsides, and disturbed areas.

Knotweed spreads by seed and large rhizomes that can reach 15-18 feet in length. It begins emerging in early spring, growing quickly and aggressively, easily outcompeting native species. When it takes over streambanks, it increases erosion by outcompeting native species that protect the soil.

Native alternatives

Tree of Heaven

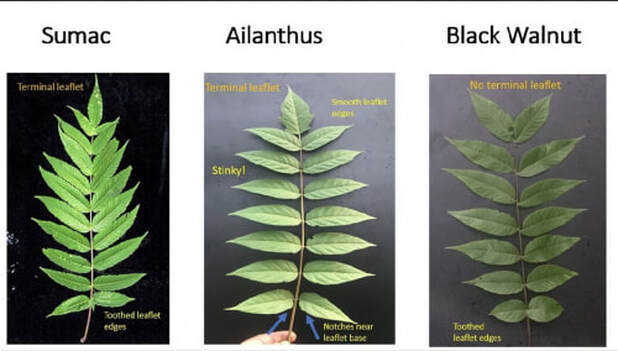

Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) was originally introduced from its native range in China and Taiwan in the late 1700s in the Philadelphia area. It was introduced to the West Coast in the 1850s by immigrants. Tree of Heaven was used as a unique, fast growing ornamental tree that could tolerate a wide range of site conditions.

This tree grows rapidly, reaching 80 feet high and up to 6 feet in diameter. It has smooth bark with several pores when young, eventually turning into light brown to gray bark with light ridges. The leaves are large and pinnately compound, reaching 1-4 feet in length with 10-40 leaflets and grow alternately on the plant. At the base of each leaflet is one or two bumps called glandular teeth. When crushed, the plant gives off a foul odor, resembling burnt peanut butter. Seeds are single-seeded samaras that often persist through winter.

This tree grows rapidly, reaching 80 feet high and up to 6 feet in diameter. It has smooth bark with several pores when young, eventually turning into light brown to gray bark with light ridges. The leaves are large and pinnately compound, reaching 1-4 feet in length with 10-40 leaflets and grow alternately on the plant. At the base of each leaflet is one or two bumps called glandular teeth. When crushed, the plant gives off a foul odor, resembling burnt peanut butter. Seeds are single-seeded samaras that often persist through winter.

Tree of Heaven produces allelopathic chemicals in its leaves, roots, and bark that limit or prevent the growth of other plants. Female trees produce more than 300,000 seeds annually and begin producing seeds as young as 2 years old. Tree of heaven has a near immediate response to damage allowing it to seed several root suckers before immediate application of herbicide can be absorbed. The trees are best treated with herbicide through foliar or hack and squirt techniques before cutting the trees for removal.

native alternatives

english ivy

English Ivy (Hedera helix) was introduced to the US as early as 1727 with European colonist. It is commonly marketed for an evergreen ground cover. English ivy has 3-5 lobed dark green, waxy, and somewhat leathery leaves. The veins on the leaves are typically lighter than the rest of the leaf. The vines climb bricks, trees, and other structures with root-like structures that exude a glue-like substance to aid in adherence. Fruits are black, resemble grapes, and contain stone-like seeds.

English ivy quickly climbs trees and across the ground, shading out native species and causing trees to collapse. New plants can grow from cuttings or stem fragments, making manual control challenging. English ivy also harbors bacterial leaf scorch (Xylella fastidiosa) which affects a wide variety of trees including oaks, maples, and elms. This plant is commonly sold as a house plant with various patterns and colors. To prevent the spread of the houseplants, make sure the plant is completely dead before discarding.

native alternatives

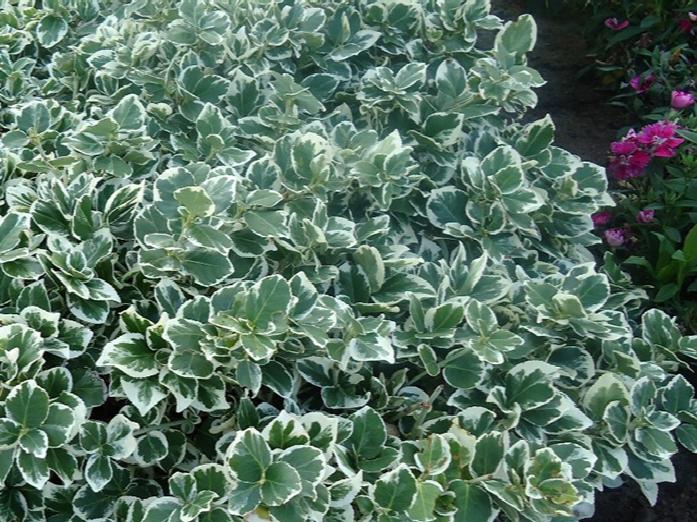

winter creeper

Wintercreeper (Euonymus fortunei) is a perennial evergreen vine. This vine is native to China and was introduced to the United States in 1907 as an ornamental ground cover. Now banned for sale and trade under the Indiana Terrestrial Plant Rule, wintercreeper is widely abundant in the state. Leaves grow opposite to each other, are oval in shape, have a glossy surface, and are less than an inch in length. Typically leaves are a dark green with lighter venation, but there are cultivars with yellows and whites.

Flowers occur in clusters of yellow-green from May to June. Fruits develop as a pinkish-red capsule containing orange seeds, maturing from September to November.

Flowers occur in clusters of yellow-green from May to June. Fruits develop as a pinkish-red capsule containing orange seeds, maturing from September to November.

Winter creeper escapes cultivation quickly because it grows rapidly even in harsh conditions and can tolerate full sun, full shade, dry soil, and moist soil conditions. The plant spreads using small roots called rootlets as the plant spreads across the ground. It is also feasted on by birds and small mammals who distribute seeds to new areas. Rootlets allow winter creeper to climb trees and rocks, reaching 40-70 feet. Like other climbing plants, they shade all herbaceous plants on the ground and climb the trees, slowly killing them by outcompeting the tree for light.

Native alternatives

privet Species

Privet species (Ligustrum sinense, L. obtusifolium, L. vulgare) are semi-evergreen shrubs or small trees that can grow up to 20 ft in height. Introduced as an ornamental shrub in 1852, it has now escaped into being a prolific invasive species. Privet species are still commonly sold for tall privacy hedges online though all species are non-native and prone to becoming invasive. Border Privet is banned in Indiana under the Terrestrial Plant Rule.

Leaves are opposite, small (about an inch long), entire margins, and oblong, with paler green and hairy undersides. Privet flowers from April to June. Flowers are fragrant and occur in terminal clusters of white to cream flowers. Fruits develop green, ripening to dark purple to black and persist through the winter. Birds and other wildlife eat the fruits and distribute the seeds.

Leaves are opposite, small (about an inch long), entire margins, and oblong, with paler green and hairy undersides. Privet flowers from April to June. Flowers are fragrant and occur in terminal clusters of white to cream flowers. Fruits develop green, ripening to dark purple to black and persist through the winter. Birds and other wildlife eat the fruits and distribute the seeds.

Privet creates dense thickets that overtake the understory and crowd out all other plants. Colonies develop quickly by root sprouts as well as spread by abundant seed dispersal through birds and wildlife. Privet can tolerate several site conditions, including bottomland conditions.

Native alternatives

POISON HEMLOCK

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum) was introduced into the U.S. from Europe as an ornamental plant. In the first year of growth, Poison Hemlock is a low-lying rosette before springing up into a 3-10 ft. tall plant in its second year. This growth pattern is referred to as "biennial". When blooming in early summer, this plant has small, white flowers that grow in umbrella-shaped clusters. Poison Hemlock is commonly confused with some species of wild carrot ("Queen Anne's lace"), but no part of the Hemlock plant is edible. A unique identifier of the Poison Hemlock is the purple spotting present on its stem.

This invasive can be found growing in areas of high disturbance, such as: along roadways, streams, trails, ditches, forest edges, and waste dumping sites.

Poison Hemlock is dangerous to humans through ingestion. If ingested in large quantities, this plant can cause death in humans, livestock, pets, and wildlife. When controlling Poison Hemlock growth, wear gloves and eye protection.

Japanese chaff flower

Japanese chaff flower is native to east Asia. How it was introduced to North America is unknown, but the earliest record of its occurrence here is from eastern Kentucky in the early 1980s. Japanese chaff flower, hereafter referred to as chaff flower, is a member of the Amaranth family. It is a perennial herb that can reach heights of 3-6 feet.

Chaff flower’s tall growth habit and dense infestations easily shade out and displace many native plant species. It is typically found in flood plains, ditches, bottomland forests and on riverbanks, growing in rich, moist soil. It prefers partial shade. However, it tolerates full shade, drier upland soils and sunnier conditions on roadsides, field edges and vacant land in urban and industrial areas. It occurs less frequently in open, full-sun environments. Chaff flower spreads quickly along waterways and public areas such as trails. It does not tolerate annual flooding or prolonged periods of inundation. Thus, in bottomlands, it is most commonly found on the first terrace above, or on the edge of, the annually flooded zone.

Native Alternatives

Native species that make great alternatives are White Vervain, Lopseed, and Red Pigweed.

Purple Loosestrife

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) is a perennial herb with long, spikey, purple flowers. It is native to Eurasia and came over to the Americas in the 1800s; either accidentally introduced via ship ballasts, deliberately brought over as an ornamental plant or its seeds were transported by imported raw wool and sheep. Purple Loosestrife blooms July to September and grows to about 5 ft. tall.

.Purple Loosestrife favors wet environments, such as freshwater marshes, open stream margins and alluvial floodplains. However, with sufficient water available, it will also grow in meadows, pastures, along stream/river bank, in ditches, and stormwater retention ponds. Purple Loosestrife can produce up to 2.5 million seeds annually and so easily spreads by flooding their environments. Purple loosestrife negatively affects both wildlife and agriculture. It displaces and replaces native flora and fauna, eliminating food, nesting and shelter for wildlife. Purple loosestrife forms a single-species stand that no bird, mammal, or fish depends upon, and germinates faster than many native wetland species

native alternatives

Native species that make great alternatives are Douglas Spirea and Swamp Milkweed.

Sericea Lespedeza

Sericea lespedeza is arguably one of the most problematic invasive species of old fields, prairies and other early successional areas managed for wildlife. Sericea lespedeza is a perennial legume native to eastern Asia that was brought to the Americas in the 19th century for erosion control, cattle forage, cover, and food for wildlife. It begins as a short, leafy plant but becomes more woody as it matures. Lespedeza grows densely on disturbed ground.

Sericea lespedeza is adapted to many different environments and produces seeds that can last in the seed bank for up to 20 years; that means that, even if you remove all Lespedeza from an area, you will need to continue managing that site for 15-20 years to true eradicate it. One technique for controlling invasives that cannot be used for Lespedeza is controlled burning; as Sericea Lespedeza responds positively to fire by growing back strong and producing even more seeds in the following season.

native alternatives

Native species that make great alternatives are Big Blue Stem, Indian Grass, and Joe-pye Weed.

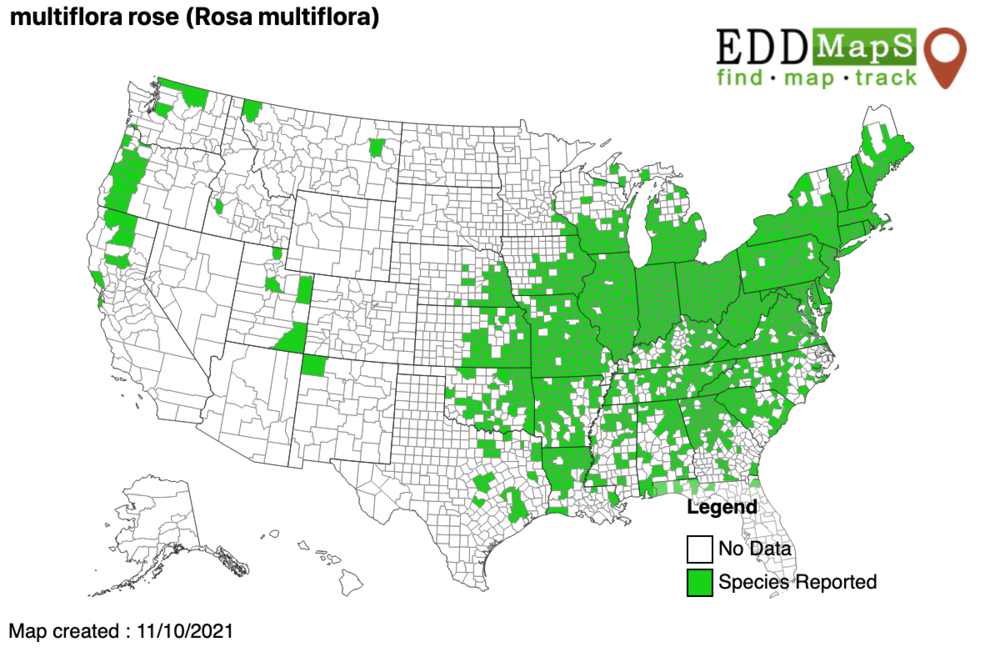

Multiflora Rose

Multiflora rose is native to China, Japan, and Korea. The plant was introduced to the United States in the 1860s for its ornamental value, was routinely used as root stock for rose breeding programs, and was promoted by the USDA Soil Conservation Service for erosion control. Multiflora rose is an invasive shrub that grows to 10-15 ft. tall and 9-13 ft. wide, forming impenetrable thickets. It has compound leaves with 5-11 (usually 7-9) leaflets. Leaflets are dark green and smooth on the upper surface; paler with short hairs on the underside. The base of each leaf stalk bears a pair of fringed stipules, which distinguish multiflora rose from native rose species. They have red thorns which turn brown as they mature.

Multiflora rose thrives in full sun and well-drained, infertile soils. It is known to proliferate in pastures, field edges, and along roadsides. Multiflora rose can also persist in part shade, although flower and fruit production is less abundant. Multiflora rose is widespread in the northeast United States, the Midwest, and southeastern states, with scattered infestations in California and Oregon.

native alternatives

Native species that make great alternatives are Pasture rose, Smooth rose, and Meadowsweet.

Japanese Stiltgrass

Japanese stiltgrass is native to Asia, including China, India, Japan, Korea, and Malaysia. It was introduced to Tennessee in 1919 as material used to package porcelain. It is an annual grass and grows to 1-3 ft. in height; it is similar in appearance to young bamboo.

Japanese stiltgrass is most commonly found in flood-plains, stream banks, moist woodlands, and areas that are prone to soil disturbances, such as tilling, mowing, and deer traffic. It thrives in moist, acidic to neutral soils that are relatively high in nitrogen. While the plant readily invades shaded areas, it is also able to tolerate full sun and a low height of cut, enabling it to persist in a lawn environment. Each plant can produce anywhere from 100 to 1000 seeds every year.

native alternatives

A native species that makes a great alternative is Nimblewill.

Nimblewill

Muhlenbergia schreberi

Muhlenbergia schreberi

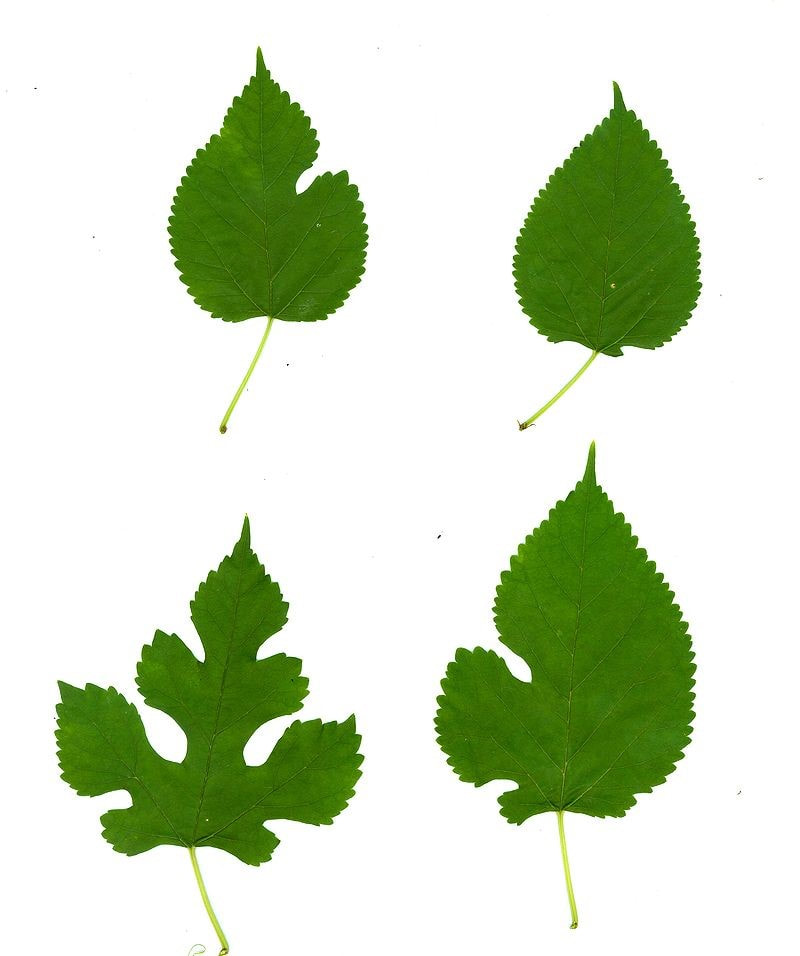

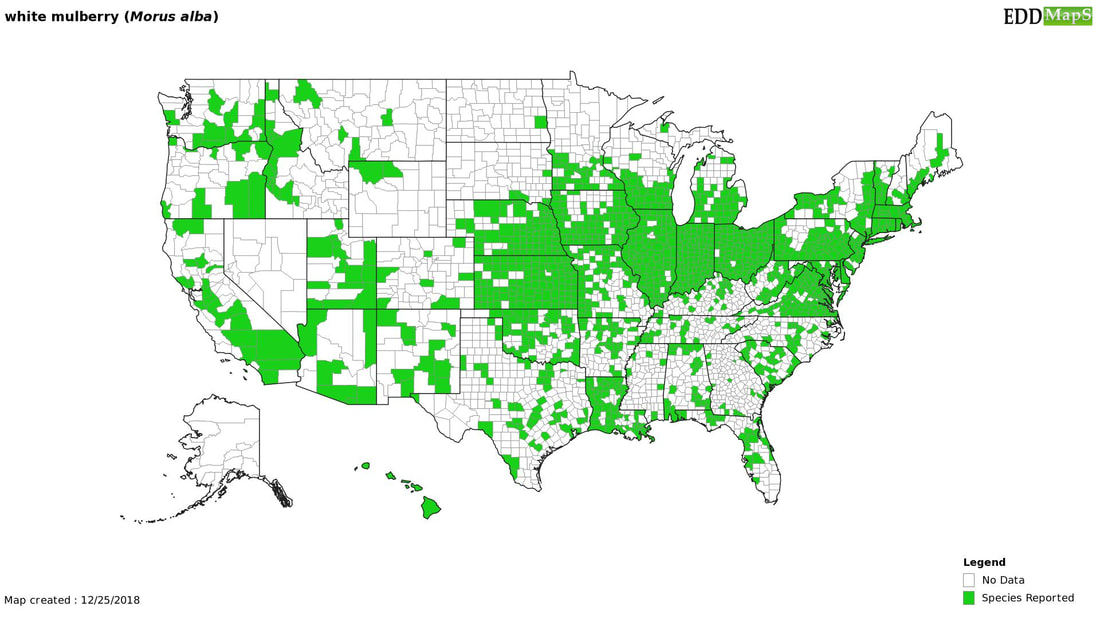

white mulberry

White Mulberry (Morus alba) can grow anywhere from 40 to 60 feet (13 – 18 meters) tall, and approximately 40 feet (13 meters) wide. Their shapes are quite variable, some can have saggy or droopy shapes, others can have rigid pyramidal or cone-like shapes. The tree has a relatively short life span, even though some have been found to live up to 75 years, most white mulberry have life spans averaging between 25 – 50 years.

This tree is native to northern China. However, it is also widely grown and cultivated across many parts of the world such as the United States, Mexico, Australia, Kyrgyzstan, Argentina, Turkey, Iran, and a good portion of Canada, as well as many other countries. The White Mulberry species prefer warm and dry soil and tend to thrive in sandy soils such as loam. The tree is considered a generally robust species reflecting the amount of disturbance and poor quality soil and environments it has been observed to grow in. The species has shown great tolerance to disturbances such as winds, droughts, and salty soils. Some research has even provided significant evidence that White Mulberry establishment is favored in disturbed areas. Even though the White Mulberry has been able to adapt to a vast variety of substantially distinctive and harsh ecosystems and environments, it prefers and thrives in sunny areas of moderate temperatures with water-depleted sandy soils.

native alternatives

Native species that make great alternatives are Red Maple, Hackberry, and Sassafras.

sweet autumn clematis wip